“A hundred times a day, I remind myself that my inner and outer lives are based on the labors of other people…living and dead…and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received.”

Albert Einstein

Some winemakers are more oriented toward the vineyard than others. This is true whether they own their own vineyards, buy fruit, or a little bit of both. These winemakers – and I will say candidly that I think they’re kind of rare – are so familiar with their sites that they notice when a single vine might be thirsty, weak, sick, you name it. They can tell you where the soils vary, sometimes from vine row to vine row. How the wind comes in at a certain time of day. How canopies can be wildly exuberant in one block, while in others they can be a bit shy. Where the vines may be vulnerable to frost, or disease pressure, and a myriad of other intimate details. They may let the vines rest up for winter, certainly, but once those tender, Kelly green buds break forth and show their faces to the sun, these winemakers are out there, in communion and courtship, with the object of their longing.

Throughout the growing season, there they are, vine by vine, row by row, block by block, acre by acre, observing and caring. And when disasters like wildfires or a crippling frost occur, sure, they worry about the bottom line. They must. But they worry even more about the well-being of their vines, every one of them, for these winemakers are quite literally connected to their vineyards and their vineyards are connected to them.

Tim Mondavi is that kind of winemaker.

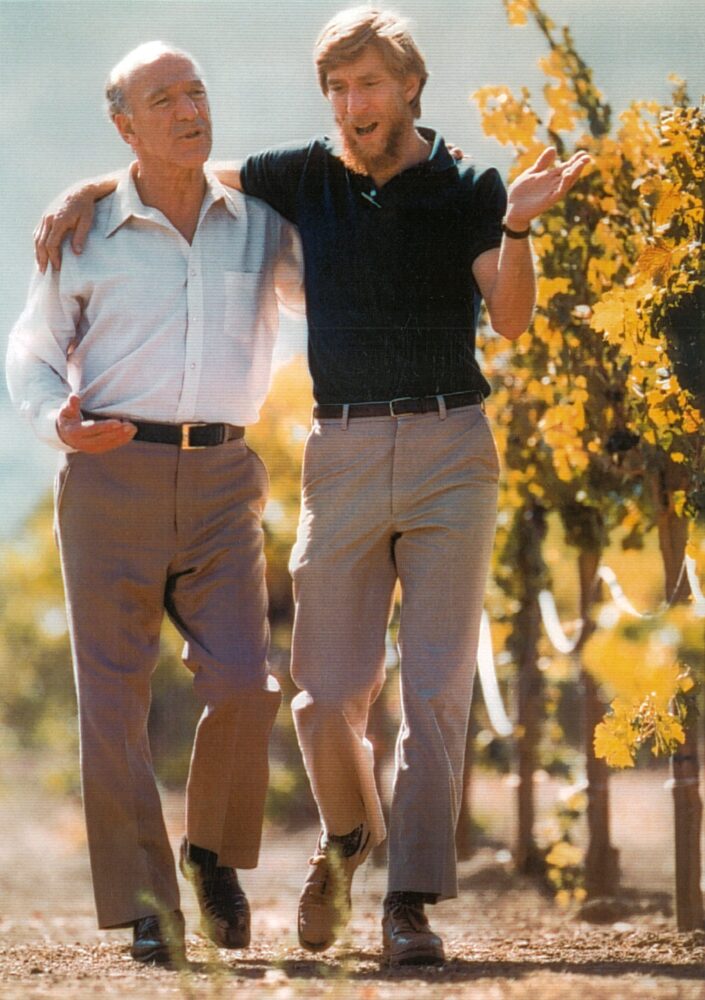

I will be sitting down with him for the next three days, as we revisit the trajectory of his career – he has just celebrated his 50th harvest – and look forward to the future of Continuum, the estate he established with his sister Marcia and his father Robert when he was 53 years old, the same age his father was when he founded Robert Mondavi Winery in 1966.

Robert and Tim Mondavi

Tim and I are sitting in a light-filled room overlooking the Continuum estate. The Lake House, as it’s called, used to be a private residence, but today, it’s where visitors to the estate are first received, surrounded as they are by his youngest daughter’s artwork: large canvases that punctuate the otherwise white walls with their iconic silhouettes of vines surrounded by negative space. Chiara Mondavi’s most recognizable painting doubles as the Continuum label: a Cabernet Franc vine that she traced, while in the vineyard, onto a large canvas.

“That’s Lupe and Salvador,” he says, pointing to a couple of men walking the vineyard rows below us. “We have worked together since the ‘80s, when they were at Robert Mondavi Winery.” He has a keen and deep understanding of the plantings at Continuum, which sits atop Pritchard Hill, a blue-chip neighborhood in the Napa Valley that includes Chappellet, Realm, Colgin, Bryant Family Vineyard, and Ovid among others.

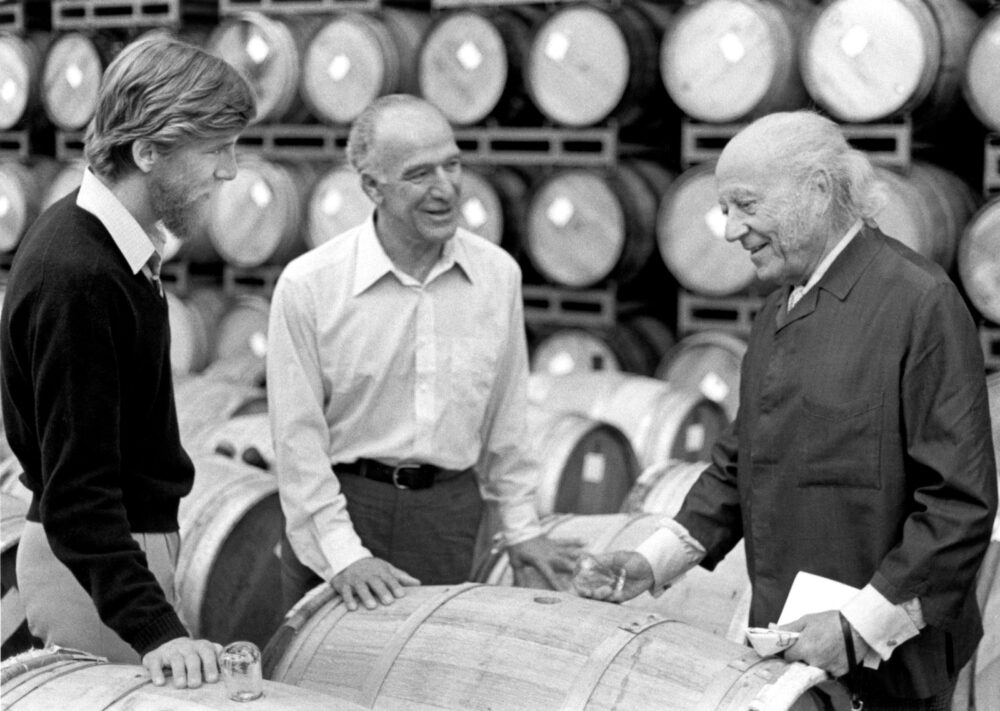

At 74, Tim is fit, bright-eyed, and present, as he was when I first met him back in the ‘90s when I was a tour guide at Opus One, the joint venture between the Baron Philippe Rothschild and Robert Mondavi. Tim was one of two winemakers there at the time. The other was Patrick Leon of Mouton Rothschild. I had kind of fallen into what I would discover was a very rare opportunity. At the time, an old Grande Dame in the Napa Valley, from whom I was renting an upstairs room, knew someone who knew someone who got me an interview there. Before I knew it, I, a poor immigrant kid who was raised on a farm and had only had one other winery job and didn’t know much about fine wine, was hired on as their second tour guide. There was still a construction trailer in the driveway when I arrived for my first day of work. My tour of the facility was conducted by architect Scott Johnson of Johnson Fain, who designed the iconic Opus One building.

I learned hospitality at that time from Robert Mondavi and his wife Margrit Biever Mondavi. They were very hands-on. We were taught how to set a tone of warmth, welcome, and discretion. Robert and Margrit were great examples and comported themselves with ease and flair.

There were a lot of parties. Lots and lots of parties. With Hollywood celebrities, artists, musicians, writers, and chefs. Orchestras. Jazz quartets. Women and men in haute couture. It was a heady time and Opus One was truly exclusive. Dinners were prepared by friends like Wolfgang Puck, Jacques Pepin, Jeremiah Tower. It wasn’t even open by appointment. We just received guests who had been invited by either or both families to visit. Back then, it was otherwise always closed. I also learned so much from the Baroness Philippine Rothschild, who stepped in to join the partnership when her father passed. She was a formidable woman, and once, when a co-worker and I set tables for a luncheon in an inelegant way, we were lightly scolded by her and told to rush and buy better linens with colors more suited to the grand salon, where most of the more intimate meals were served. She taught me that God is in the details.

Tim, Robert, and Baron Philippe de Rothschild at Opus One

And then there was Tim. Lean and thoughtful, with a shaggy mop of dirty blonde hair, he was often quiet and observant, though he could be talkative and engaging if the mood struck. I mention this to him, how he seemed quite ruminative at the time. “My father was very outgoing. My grandmother was very outgoing. The grandfather that I knew, the Cesare that I knew, was much quieter and a man of few words. So, I’m more like my grandfather, in that sense, quieter,” Tim says.

Once, I got up the courage to speak to him because I’d heard that he was into Buddhism, as was I. I don’t remember our conversation, but when I bring it up to him now, he recalls those earlier days. “I started going to these Monday night sitting sessions at the Spirit Rock meditation center in West Marin, studying Mahayana, a subset of Buddhism,” he says of that time. “And I found a number of the speakers there to be very interesting, but most importantly, Jack Kornfield. I was lingering on his every word. And I had gotten Stories to Nourish the Spirit and the Heart. It’s such a great book. I need to get another copy of it, because it’s been quite some time. I gave that book to each of my children. And I also gave them another book by Houston Smith, a philosopher. I met him, two or three times, and would seek him out at Esalen.”

Smith’s book, The Religions of Man, which he later updated to The World’s Religions, left an enduring impression on Tim. “It is so well written. It’s about each of the six, eight religions of the world that he selected by virtue of the number of adherents that would be following it. And ultimately, he says, all of them come down to a basic thing: It’s the same things that Christ taught, that Buddha taught, that all these great wisdom teachers teach us: about having respect for one another. Even the Dalai Lama says, any religion will get you there. Go with what works for you, but adhere to the principles of respect, love, and celebration of how lucky we are to be in this incarnation. We are all connected. I think this is very important,” he says.

It’s nearly impossible to conceive of today’s Napa Valley without the influence and imprimatur of the Mondavi family. When Robert Mondavi’s parents, Cesare and Rosa, bought Charles Krug winery in the early 1940s, it instantly became a communal hub through which visitors frequently passed – friends and family, visiting winemakers, travelers – for hearty Italian meals, wine poured in abundance at the table, and conviviality. Come, let us feed you. Come, let us celebrate life together for these few moments around a generous table. It was into this rich, vibrant, emerging culture that, in 1951, Tim Mondavi was born.

Prohibition had ended only 18 years earlier, and even though there were 121 wineries in the Napa Valley by 1919, there were only nine in operation when Prohibition ended in 1933. The time was ripe for the re-emergence of wine culture, and the Mondavi family was well-positioned to help ignite a new era.

As a boy, Tim Mondavi could lose hours playing in piles of grape pomace, warm and pungent under the sun. “I’d throw the grapes up in the air and have my T-shirt completely messed up the first day of harvest,” he says. “I would go out with Uncle Pete, and he would collect grapes into a canvas sack. He would crush them into a cylinder and put the juice into these floating hydrometers that would measure the specific gravity of the juice, to see what the sugar was. And so it was great fun to do that with him before the development of refractometers.” When he got tired as a boy, he’d nap under the canopy of vines out behind the winery.

When their parents entertained, Tim and his sister Marcia were put in charge of washing and drying the wine glasses, and a young Tim would play sommelier tableside, making sure the glasses were refilled. “Everybody was expected to work. Children back then were expected to be seen and not heard, but to support what was going on.”

By the time he was 24 years old, Tim was making wine at his father’s namesake winery, The Robert Mondavi Winery, which Robert had founded in 1966 after he and his brother Peter had a falling out. The brothers repaired their relationship in later years.

Robert Mondavi was among a handful of pioneers who sparked the imagination of the Napa Valley, who reflected back to itself a vision of what it could be: a blue-chip region like others in the world where wine, food, art, and hospitality converged to become cornerstones for a robust culture.

Parallel Lives: Tim and the Napa Valley come into their own

Tim is dressed casually, though sharply. His clothes fit him well. Even as a young man, he always cut an elegant shape. We’re getting to know each other again after so much time. For even though I’ve run into him at dinner parties here and there over the years, this is the first time in over three decades that we’re catching up.

The Mondavi family name is so synonymous with wine in my mind that I ask Tim if, as a boy, he wanted to be something else when he grew up, or did he just know that he’d be in the family business? “Wine was something that we did,” he says. “It nourished us intellectually, enriched our lives, and it was the way we made our living. It was also the focus of all our discussions at dinner. My father was always proselytizing, getting all of us to be excited about wine. He would start his sentences, and eventually we would finish them, and the paragraph…and the book, basically, because he would repeat the same thing. And so we had that in spades in that it was kind of non-stop. He was very charismatic, to put it mildly. And now I think my children have carried on that charisma as well.”

I wonder aloud what it must have been like being Robert Mondavi’s son. Robert Mondavi was The Man back then. He was synonymous with the Napa Valley and possessed great charm. Supremely confident, he entered a room as if he belonged there and treated others as if they belonged there, too. His energy seemed magical to me. So, I ask Tim if he had imposter syndrome growing up with a dad with so large a cultural reach. “People would often say, ‘Tim, you know you’ve got huge shoes to fill. Your father is such an amazing man.’ And, I would cringe and say, ‘Yeah, I know you’re right. I know. I know. I know.’ Or they’d say, ‘You’ve got a huge shadow to get out from under.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, I know. Absolutely.’” With a charismatic visionary as a father, Tim felt pressure from himself and others to live up to the promise of that expansive Mondavi vision. “Later,” he tells me, “I came across a quote attributed to Isaac Newton that said, ‘If I have seen further than others, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’ This was a very powerful and liberating idea.”

Newly armed with this broader perspective, Tim deepened his commitment to the family business, working alongside his father and brother Michael to build upon his father’s vision of bringing fine wine culture to the Napa Valley.

The narrative arc of Napa Valley wine history begins in 1861, when Charles Krug Winery was founded. Maybe because Tim grew up there, his own storytelling around Napa Valley begins with the rush of German immigrants who, in quick succession, established Napa wine culture. In 1862, Schramsberg was founded, followed by the Beringer Brothers establishing their eponymously named winery in 1874. From there, Inglenook came into being in 1879. “These are the people that came with a culture of winegrowing and wine appreciation,” he says.

The modern era of the Napa Valley practically mirrors the trajectory of Tim’s life and career. When Robert Mondavi established his winery in 1966, most cellars in the Napa Valley were still reeling from the lingering effects of Prohibition, which lasted a long, arduous 13 years. “After that period of time”, Tim tells me, “There was the loss of a lot of brain trust. People had to recreate the wheel because, at the end of Prohibition, cellars were left with old equipment and old tanks that had not been maintained or kept clean. And so, as a result of that, microbial challenges were present. Oxidation happened often. You could have a lot of difficulties in a resulting wine.”

It was once again a young industry after Prohibition ended, so winemakers went to U.C. Berkeley and U.C. Davis, searching for solutions. “Winemakers would say, ‘I’ve got this microbial problem.’ And microbiologists would tell us, ‘Well, okay, with most microbes, you either shift the pH – you can add acid – or you can filter them out, to get rid of the microbes. And so, there was a focus on repression of faults, and when you repress faults, you also can repress virtue. My father recognized that the biggest problems were due to off, unclean, or old cooperage. Robert Mondavi Winery was the first winery to have stainless steel tanks and new German ovals for the aging of white wines, and for fermenting wines. And new French oak barrels. Suddenly people began to say, ‘Wow, these wines are so much better!’ There was a huge love affair with new oak that dad basically began.”

During a trip he took to Bordeaux in 1962, Robert Mondavi learned that the first-growths were utilizing new oak barrels, as unclean and off barrels were a phenomenon not just in the United States, but all over Europe as well. “In Europe,” Tim says, “people were buoyed by tradition or trapped by tradition, depending upon one’s perspective. Wine quality was quite variable throughout the world, not only in California.”

Robert Mondavi returned to California with new information and a great willingness to experiment and innovate. “New oak was synonymous with attempting to do great things, new things,” Tim says. “And like how new toys for a child can become overused, new oak was overused at the time. We didn’t know how to properly clean empty barrels back then. We couldn’t then. We didn’t understand the technology. It took a while for us to figure out how to care for empty barrels properly. Now we do, and so we can use neutral barrels quite favorably.”

Winery tanks to cave portal

Blue chip wine growing regions are as much about local culture as they are about fine wines. Long before shows like Top Chef, Robert Mondavi was creating opportunities for home chefs and professional chefs to interact and engage in the appreciation of fine food. “My father had this brand-new idea for cooking classes. Back then, Italian food wasn’t really recognized as elegant food, but French food was. John and Jackie Kennedy had just been in the White House, and they had French chefs with their Michelin Guide stars and big toques as tall as their egos. And so, there was a lot of fanfare about French food. Italian food could be equally fabulous, but people just took it for granted.”

Robert Mondavi recruited Julia Child and numerous three-star Michelin chefs to teach cooking classes for the public and emerging chefs. “Daniel Boloud said that he came to America because as a young chef, he would go apprentice at all these fancy restaurants in France, three-star restaurants, and the chefs were all going to the Napa Valley,” Tim recalls. “When he asked them where they were going, they’d say, ‘To Robert Mondavi Winery. So, he came and did a big event at Robert Mondavi Winery, a long time ago, when we were introducing our appellation wines. More recently, when we were celebrating our 100th anniversary, he said that Dad, whom he had a lot of regard for, was the reason that he ended up here in America.” 1n 1981, Robert Mondavi and Julia Child, along with Richard Graff and a handful of others, established the American Institute of Food & Wine, a 501 (c) (3) non-profit and public charity “founded on the premise that gastronomy is essential to the quality of human existence.”

Culture alone, however, does not make an industry. Standards, guardrails, and boundaries help to shape an industry and, as a result, the region that gives it life. Tim was instrumental in helping to define and delineate what would become the Napa Valley AVA, or American Viticultural Area. “Wine has been buoyed by many advancements, but wine has been around since the development of civilization. When we shifted from hunters and gatherers to raising crops … that kept us in the same place. And wine was very much a part of that. And so, if you look at all the historical places, they are around river basins where you would be able to have good agriculture. That’s where the towns were, and ultimately, vines took the shyer soils, and fruits and vegetables took the richer soils,” he says.

“I was on the board of the Napa Valley Vintners when the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (now the TTB) informed us that if we wanted to use the Napa Valley name going forward, we would need to validate its use. They had just established the American Viticultural Area designation law in 1980. The first appellation in the United States was Augusta, Missouri. Napa Valley would become the second. Chuck Carpy was the Chairman of the Board of the Napa Valley Vintners at the time, and I had enormous regard for him,” he says.

Up until that point, winemakers used “Napa Valley” as a designation on their wine labels, while producers in other regions were using “county” – Sonoma County, Yolo County, Mendocino County. But Napa County never felt appropriate because vineyards were planted mostly in the valley of Napa, not the surrounding townships.

“A valley is usually demarcated by a watershed of two ranges that is drained by a river that oftentimes carries the name of that valley,” Tim explains. “The Rhine Valley, for example. So, the Napa River watershed is how we defined it, and the Napa Valley AVA took its name from the watershed. And the two ranges became the ridgeline of the Vaca Mountain Range and the Mayacamas Mountain Range.

At the time, though, Tim was bothered by the fact that there were some viable growing regions within Napa County that were outside of the watershed. He felt they, too, deserved to use the “Napa Valley” designation. “The Napa River watershed excludes Chiles Valley…and valleys that are within Napa County, but outside of the river watershed. That’s taking something away from the people who helped make Napa Valley. I said, ‘This is wrong. This is unjust to take something away from people that were farming before you were here, their livelihoods are dependent upon it.’”

Holding firm to this position, Tim and his colleagues at the Vintners Association set about developing Napa Valley’s sub-appellations, identifying Calistoga, St. Helena, Chiles Valley, Rutherford, Oakville, Yountville, and Napa proper as sub-regions of consequence. As the years progressed, additional sub-appellations would include Atlas Peak, Carneros, Coombsville, Diamond Mountain, Howell Mountain, Oak Knoll, Spring Mountain, Stag’s Leap Mountain, Wild Horse Valley, and Yountville.

Before AVA status could be granted, a case had to be made as well for the legitimacy of Napa Valley’s historic relevance to wine. Tim hired the late, old-school historian William Heintz, to compose the region’s historical data and legendary, consensus-building lawyer Richard Mendelson to assist in further delineating the appellation system as it pertained to the Napa Valley. The Napa Valley was granted AVA status on February 27, 1981.

Having helped to develop Opus One, Tim played a significant role in establishing additional collaborations to oftentimes stunning results. A partnership with Errázuriz resulted in the creation of Sena, a collection of Bordeaux-varietal wines from the Aconcagua Valley of Chile. In 1993, Tim joined forces with the famed Frescobaldi family, and under the guidance of Vittorio Frescobaldi, created Luce. Alongside Vittorio’s son Lamberto, Tim created exceptional wines under that label. Then, in 1999, Robert Mondavi purchased Tenuta dell’ Ornellaia, and in 2002, the Frescobaldi family was brought into partnership with that iconic brand.

In 2004, the Robert Mondavi Winery sold to Constellation. Family squabbles, disagreements about growth and positioning, and numerous other influences led to a decision that would come to represent the end of an era for the Mondavi family in the Napa Valley.

The next chapter, though, was right around the corner.

Tim and Marcia in the vineyard

The Horizon Line: Continuum

That same year, when he was 53 years old, Tim established Continuum, alongside his sister Marcia Mondavi Borger and his father. Up until then, he’d mostly worked with fruit from valley floor vineyards, including To-Kalon, arguably one of America’s most iconic vineyards, yet his aesthetic sensibilities were calling him to the hilltops.

“Petit Verdot and Cabernet Sauvignon do well in the valley floor, while Cabernet Franc and Merlot do least well there. Cabernet Franc and Merlot do very well up here on Pritchard Hill. I think they do better here than the valley floor because vigor is lower. That’s one element, but there’s got to be an influence based on the minerality of our soils as well. Bordeaux writ large is about 60% Merlot, 40% other Bordeaux varieties. The Médoc is completely different. The Médoc is 85% Cabernet Sauvignon, with the balance being a little bit of Merlot and Cabernet Franc, and even less Petite Verdot. So, yeah, we’re much more like Saint Emillion here, whereas the valley floor is much more like the Médoc.”

The Continuum wine we had at lunch the previous day was breathtakingly pretty. Surprisingly so. It’s not that I don’t expect them to be. Tim’s wines while he was at Robert Mondavi Winery and Opus One were showstoppers. But I’m not as familiar with Continuum, and I guess I was expecting a well-made, but perhaps big Napa Valley red wine. So many of them that I have these days are a bit big for me.

Instead, Continuum has luminous, lifted and bright aromatics, which lead to a palate of refinement: sublime texture, an intentional and precise flavor profile, and a long, long finish. They’re affirming for anyone who loves balance in wines and the Napa Valley, and who longs to experience elegance and finesse in a Bordeaux-varietal wine from this region. “I’ve been accused and criticized for being Francophilic in my orientation,” Tim says, “as opposed to embracing these big, bold, you know, blowout wines. And, yeah, I am more Francophilic. I do like wines of more elegance and finesse. And so now we are learning how to get more of that than ever before. We have been doing a lot of research and documentation of the individual blocks on the run up to harvest, doing all the analysis of that, and now we’re making sense of those trends and acting on those trends in how we care for the vineyards, how we harvest, how we vinify. It’s reacting to what is. And the longer you do that, the more you can refine the process. Refine. Refine. Refine.”

Today, we will be tasting components of the 2024 vintage that will eventually comprise the final Continuum blend. It is the 21st vintage for Tim at Continuum. I arrive a few minutes late and must navigate the impossibly quiet hallways and rooms of Continuum before I can locate Tim and his team. Over the past couple of days, Tim has referred to the Continuum production facility as a chapel to wine, or a temple to art. I wonder to myself why it doesn’t sound precious when he says this, as on paper it could read that way. Instead, he delivers this with humility in his tone, like he feels lucky to be there. “I would say artistic wine is an expression of man’s harmony with nature. We do have to be observant. The best science is the study of nature at its finest. And ultimately, that is the ultimate truth: to understand what nature is trying to tell us. A respect for nature is fundamental,” he tells me.

And the aesthetics of the Continuum facility mirror the natural world. Subdued natural tones are evident throughout the winery. Any stainless steel railings have been bronzed to add warmth to the environment. Walls are muted. Artwork is minimal. “There’s this Zen simplicity that I wanted to have in the cellar,” he says. “It was a stated objective to have it be simple, easy to clean, and workable. When you’re there, you smell wine or just cleanliness, not detergent, not some sort of synthetic fragrance that makes it so you can’t smell the wine. I hate those air fresheners. Just open the windows,” he says.

“During harvest, it is naturally chaotic. And one of the things that I love about the Hispanic community that works in the vineyards is that they sing lovely songs,” he continues, “and they’re much more musically oriented than others, and I think that’s fabulous. And so, in the cellar, oftentimes at the beginning of harvest, we will have Hispanic music playing, and it’s happy, joyous.” When the wines have been barreled down to be raised, Tim likes “meditative sounds as the wine is resting and evolving.”

It is very quiet when I arrive at the component tasting. Lining countertops that run along both sides of a long room flooded with natural light are 44 different components of the 2024 vintage that we will taste through. Tim holds an estate map with vineyard blocks broken down with tremendous specificity. Different components reflect differing vessels (concrete fermented, bin fermented, new oak, neutral oak, different cooperage) and rootstock, grape variety, picking date, brix levels, levels of TA, pH, VA, MA, and so on. It’s all a bit overwhelming for this taster, but Tim and his team appear relaxed, confident. Occasionally, someone will call out a certain component that is pretty, or especially lifted, or shy for whatever reason. But they are otherwise turned inward, focused. I’m starting to understand the chapel thing as, for a workspace, this room is vibey– it welcomes reflection and concentration.

I tell Tim about a 1976 Robert Mondavi Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon that I had last year that was a revelation. Great tertiary flavors. A supple texture. Time-integrated tannins. And mysterious, nuanced aromatics that recalled frankincense, a walk through the forest just after rain, violets and other fragrances that took me right back to old library visits, rose gardens, leather shoes, and so much more that the sense of smell conjures and then ushers through the portals of memory. “I think bottle aging is really important,” he tells me. “I love our wines when they’re young, and I think we are understanding how to raise the vineyards properly through organic farming and improving the resiliency of the vineyard, reducing the stress. The vines are better able to evolve the phenolic material and to develop the delicacy of fragrance that is so pretty here, just very, very expressive and energetic. Once the wine is beyond any bottle shock that might be there, say, after a few months, then it just begins to blossom, and it continues to evolve, and the palate develops much more length and tenderness and complexity. It’s those evolved flavors that go from fresh and floral and pretty to more wizened that impart more depth of character, more soul. And so, it’s like seeing a young boy or girl, you know, they can be very handsome or beautiful, but they don’t have the nuance or wisdom. I think the manifestation of beauty is also in that spirit.”

He gets a dreamy look in his eyes when he tells me about some folks he used to admire when he was younger. “Mara Louise Detert was always such a beautiful, intelligent woman. I thought of her as the Queen of To-Kalon, because her home was there on the Detert vineyard at the end of Walnut Drive, and I thought that she was so elegant. And I adored her husband Gunther, who was a very handsome, thoughtful, smart guy, a very capable attorney, and they were such a beautiful couple. And I think some people are always beautiful, even as they age, you know, and I think that to be able to have that radiance come through and be expressed in a deeper, more profound way is fabulous and that’s what happens when one ages a fine wine. The layers of expressiveness of beauty deepen.”

The views from Continuum are expansive. On a clear day, the San Francisco skyline is visible. Tim points out a few highlights of the estate vineyard, which the family has named Sage Mountain Vineyard. “You look around and you see the vegetation: California Bay Laurel, wild sage, Manzanita, scrub oak, chamise. Very different growth than on the Mayacamas range. So very, very different. And so, it makes sense that the vines are different, the wines are different.”

He draws an imaginary line from the Mayacamas range on the other side of Napa Valley to Pritchard Hill, which rests at the feet of the Vaca Mountain range. “If you just think about the cross section,” he says, “you draw a line from the top of Mount Veeder, all the way down to the Carmelite monastery, and then across through Robert Mondavi Winery to the Napa River. Cross the river, and then there’s a creek that’s there, as well. But then you come up on the side slopes of the Rudd estate, and Screaming Eagle and it’s red, rocky, volcanic soil. And then there’s Dalle Valle and it gets redder and more volcanic still. I think that there’s something magical about volcanic soil. Volcanic, well-drained, rocky soils give wines of great texture and minerality and vibrancy. And I think we understand how to manage the land better than ever before and manage the vines and then vinify those individually. Every block has its own personality. And that’s the thing that’s fun. It’s like four-dimensional chess, because time is important. You learn over the years, over the decades, and you see patterns, and you figure out ways of dealing with these patterns. So yeah, it’s a magical business that we’re in.”

If Tim is anything, he’s a farmer. For all the notoriety and high scores and world travel and general fanciness, he is, essentially, still a farmer. “I love, love just driving through the valley, seeing farming. I love the existence of the fact that we’re still working the land. We’re still doing that. I was in Santa Barbara recently. And I love Santa Barbara, because from the plane, you could see all these orange groves and lemon groves and vineyards tucked into the hills. I love that there is a reason for an area to be that tied to agriculture. There is something that is very powerful about that. It is being in touch. Thomas Jefferson said that all men should be farmers, because it keeps you humble. And I think if you are a farmer, then you realize there’s something much greater than yourself. You don’t control everything, and there is something that is humbling and grounding and maybe even liberating about that. There are many lessons that nature teaches us. And so, when you see people working the land, it is beautiful. It speaks of a respect for nature and for engaging with nature. And an inclination to care for one another. Nourishing people with food crops or beverage nurtures the soul as well as the body. That’s important. So, it kind of makes me happy when I drive through the Napa Valley, when I drive through or fly over Santa Barbara and see all this agricultural beauty,” Tim says.

The Next Generation: Sentium, RAEN and the future of Continuum

Of Tim’s five children, all but one is involved in the wine business. Sons Dante and Carlo established RAEN in 2013, a project based on the Sonoma Coast, focusing solely on coastal Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Dante handles the business side of things while Carlo is the winemaker. RAEN stands for Research Agriculture Enology Naturally, and in under a decade, the brothers have built an emerging brand that has garnered the attention of critics and sommelier culture. At lunch one day, Tim pours a 2023 RAEN highlighting Freestone-Occidental fruit. It’s lifted, pretty, and oceanic. Tim looks delighted as he swirls his glass. “Fort Ross-Seaview is perhaps leaner than the Occidental, but they’re all floral and vibrant and absolutely fabulous,” he says. I comment that he must be proud of Carlo and Dante for how well they’ve built their brand so far. “I’m very proud of all of them. This is very fruit forward right now, but as it ages, it will develop more of those tertiary flavors that I love. Texturally, it’s quite lovely. Quite a finish, this one. This is whole cluster, a very high amount of whole cluster. They seem to be managing that well. There’s none of that Mentholatum or weirdness on the nose that you sometimes get from some wines with too much stem inclusion.”

Carlo is effusive and highly social, like his grandfather Robert. Dante strikes me as a bit shyer and retiring, like Tim, though like his father, he pushes through the shyness and possesses impeccable, old school manners. Carissa, Tim’s eldest daughter, is the first of the third generation to join Continuum. There, she oversees nearly every aspect of the business except for production, including hospitality, sales, and administration. She travels broadly and often, representing the family around the globe. She has a delicacy about her that I’ve not yet experienced in the family. At first, she appears to have an almost tentative orientation to the world. Later, as I get to know her better, I discover that she’s actually quite strong and empowered. What I’ve been picking up on is her deep consideration and sensitivity to others.

Her younger sister Chiara is perhaps best known in the Continuum universe as the artist behind the now iconic label. She is wildly gifted, I discover, in the vineyard and the cellar as well. Soft-spoken, thoughtful, and reflective, she pours her Sentium Sauvignon Blanc for me almost reluctantly, as if she’s not comfortable with the attention.

The Next Generation: Brian Mondavi Borger, Carlo Mondavi. Carissa Mondavi, Dante Mondavi, and Chiara Mondavi

The wine, it turns out, is a game-changer. Sourced in Mendocino County from organically farmed old vines that were planted between 1940 and 1960, it’s reminiscent of the wines made from the Loire by the late Didier Dagueneau in the 1990s and early ‘00s under his Silex label. The Sentium brand is a distinctly fourth generation project. Chiara is the winemaker, and she is joined by Carissa, as well brothers Carlo, Dante, and Dominic, and cousins Caitlin Mclean and Brian Mondavi Borger, Marcia’s children, who all serve as partners. Brian divides his time between Sentium and Continuum, where he is involved in the daily operations of both brands. If there is a throughline connecting Continuum to Sentium and RAEN, it may be Tim’s strong lineage and influence on his children. Clearly, the next generation is resolved in pursuing greatness, and there’s a sense they understand greatness takes time. Both Sentium and RAEN are growing slowly and, compared to many brands, quietly.

Dominic Mondavi, Tim’s third son, is a successful graphic artist who has forged his own path away from the wine business. “They’re all lovely in their own way,” Tim says. “Dante has this relatability and openness I really enjoy. It’s very sweet and disarming. He’s more on the business side of things. Carissa is a strong woman. She is obviously very capable, and yet she is rather sensitive and thoughtful. Chiara has an artist’s sensibility. She is the observer, the interpreter. Carlo is a little bit of everything. He’s smart, thoughtful, open, social. He’s always on the go. Dominic is also an artist. And he’s so well-read. He always has been. When he was younger, he practically read a book a day. I would tell him; your reading is going to give you a world that others haven’t seen. It will be an incredible strength to you in the long run, and it has been.”

As our time together comes to an end, Tim and I embrace before he returns to the component tastings, which will last a couple more days. It’s a bit of a full circle moment for me, and as we’re saying goodbye, I surprise myself by getting a little choked up. Then Tim smiles, bearing a deeply stained purple smile, and I head out, grateful.