Days after starting my official role with JebDunnuck.com last October, I received a compelling invitation to come to New York City and taste the wines of an exciting Ribera del Duero producer, Dominio de Es, featuring two verticals of its ancient-vine Tempranillo-based wines, La Diva and La Mata, going from the very first vintage to barrel samples of 2023.

Lucky for me, it also ended up including a small vertical of Carravilla. Collectively, these are some of the most exciting, elegant and energetic wines I’ve tasted, made with remarkable focus and skill from a remote pocket of Spain’s Ribera del Duero.

The invitation came from Mannie Berk of Rare Wine Co., who noted Dominio de Es’s pedigree as one of the two most expensive and rarest wines of the region (the other being Pingus), with only one to two barrels made of each. Winemaker Bertrand Sourdais would be there.

I forwarded the invitation to Jeb asking if I should go. His immediate reply? “I would.”

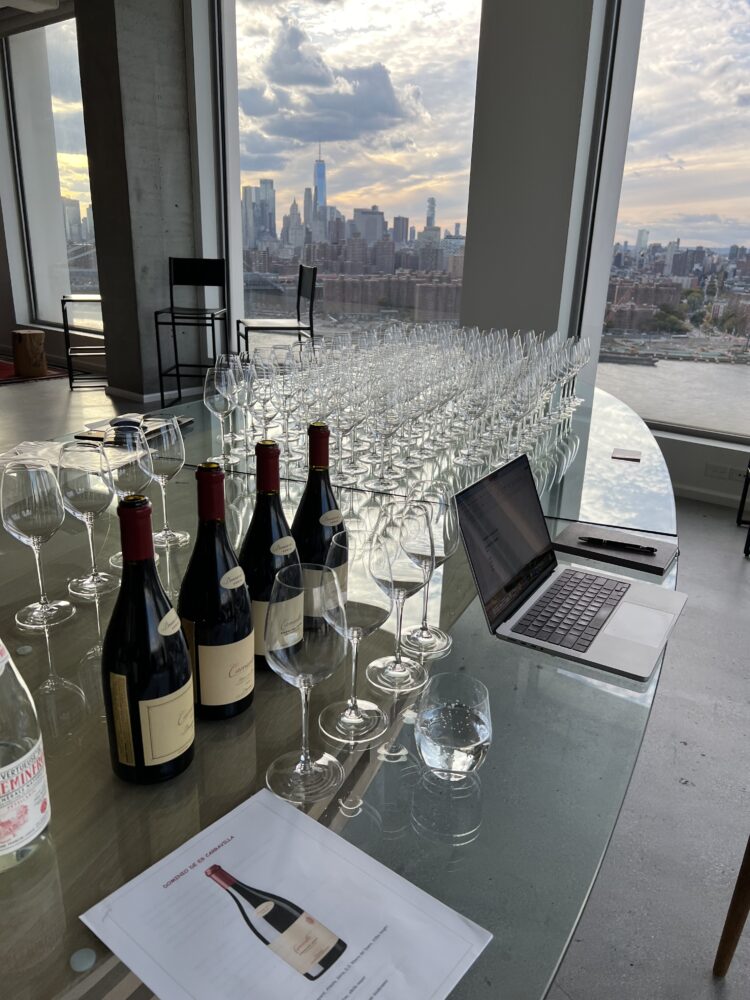

That’s how I found myself October 8, 2024 in Brooklyn, on a top floor with spectacular views of Manhattan, face to face with Sourdais, who had flown in from Spain during the middle of harvest for one night only.

Sourdais is from Chinon, where five generations of his family have grown grapes and made wine. In 1996 and 1997, he worked with Château Leoville Las Cases and Château Mouton Rothschild. In 1998, he collaborated with Alvaro Palacios in Priorat and in Chile. From 1999 to 2010, he served as co-creator and technical director of Dominio de Atauta in Ribera del Duero, while maintaining ties to his family’s Domaine de Pallus in the Loire Valley.

In 2010, Sourdais co-founded Bodegas Antídoto in a small town in Ribera del Duero called Soria; a year later he founded Dominio de Es to further explore the area’s intrigues.

The small village of Soria is unique in the region for its cold temperatures, with both a continental and mountain climate. It’s also brimming in ancient, ungrafted Tempranillo/Tinto Fino vines. In a higher eastern part of Ribera del Duero between two mountain ranges, Sourdais likens it to the Jura region of France, cold and somewhat deserted, calling it “the rooftop of Ribera.”

Nobody knows why there are so many ancient vines in this tiny village in the middle of nowhere (Sourdais’s words), but he thinks one of his plots, La Diva, is probably 200 years old based on stories older villagers have told him about their grandparents knowing these vineyards.

Sourdais was working in Bordeaux when he became interested in Spanish life and Spanish wines. Having grown up and worked in France, he says the climate is 100% different in Spain, where vegetation is very dense, having adapted to protect itself from the sun and the harsh conditions.

But when he first arrived in Soria, he didn’t see vineyards.

“I grew up in the vineyards of France, where you see 100% vineyard, vineyard, vineyard,” he says. “This is not the case in Spain, especially Ribera del Duero.”

But he soon saw the magic. Still, he says he was stupid at 23 years old.

“I was arriving from France and straight from school thinking I knew everything,” he admits. “But the old agriculture was (being threatened by the) seduction of modernization with herbicide and things to fight disease.”

Sourdais started Dominio de Es in 2011. Today it produces about 10,000 bottles. He is finishing a new gravity-flow winery in the middle of the village, which has a population of about 2,500 people. His dream is to make 25,000 bottles and manage that amount with just three people.

“I love to control everything,” he says. “This is the way.”

Working with significant acreage of ungrafted Tinto Fino/Tempranillo vines sitting in, depending on the altitude, pure limestone, pure sand with limestone and/or pure clay with limestone, Sourdais’s viticultural standards include no chemical fertilizers, herbicides, or pesticides and incorporating some elements of biodynamic farming.

He makes three wines – Caravilla, La Mata and La Diva – always asking himself, what is a grand cru?

“For me, I have to have sensational emotion, finality, I want this wine, one unity of terroir – soil, climate, vegetable – to have a perfect connection that can touch my vibration and emotion,” he describes. “In Spain, I don’t agree vineyards have to suffer to be great. Spanish vineyards have to feel well and not feel stress to do their best.”