It’s a blustery day in a remote location in California’s San Benito County when I meet up with Kelli White for our interview. I’ve been wanting to interview White since 2015 – the year she released her comprehensive book, Napa Valley Then and Now, a 1,255-page tribute to America’s most esteemed winegrowing region. It’s a book I reference often, and I’ve long admired White’s work as a sommelier, author and educator. Over time, I’ve run into her at Press, a restaurant in the Napa Valley, where for years she presided over the nation’s deepest collection of uncommon, old Napa Valley wines. I’ve watched her expertly decant aged, rare bottles with confidence and a steady hand. We often rub elbows with the same colleagues. So I want us both out of our element for our first, in-depth chat.

We’ve been together now for a few hours, journeying through the remote foothills of the Galiban Mountain range. At one point during our visit, we spot a bobcat meandering through a little-known vineyard, and White asks to get out of the truck so she can get a better look. Her thin, lithe frame makes its way lightly through a row of cover crop. She gets fairly close to the bobcat before it runs off into the nearby foothills. She snaps a few pictures of it sitting there in defiance before she runs back to the truck, looking like an adventurous 12-year-old girl away at summer camp.

It’s getting chilly out, and we soon retire indoors where we stretch our legs, pour ourselves some plum wine, and put on some music. White chooses Karen Dalton, an artist I’d never heard of until now. Dalton, it turns out, was a contemporary of Bob Dylan’s and one of his favorite singer-songwriters and guitarists. She never got the recognition she deserved and died in 1993 at the age of 55, in a mobile home, from an HIV-related illness. White wants me to hear her favorite Dalton song, “A Little Bit of Rain,” and so she puts it on. I let the song work its magic. It’s a heartbreaker, and after it’s over, White just looks at me and says, “That line: ‘A little bit of rain’…”

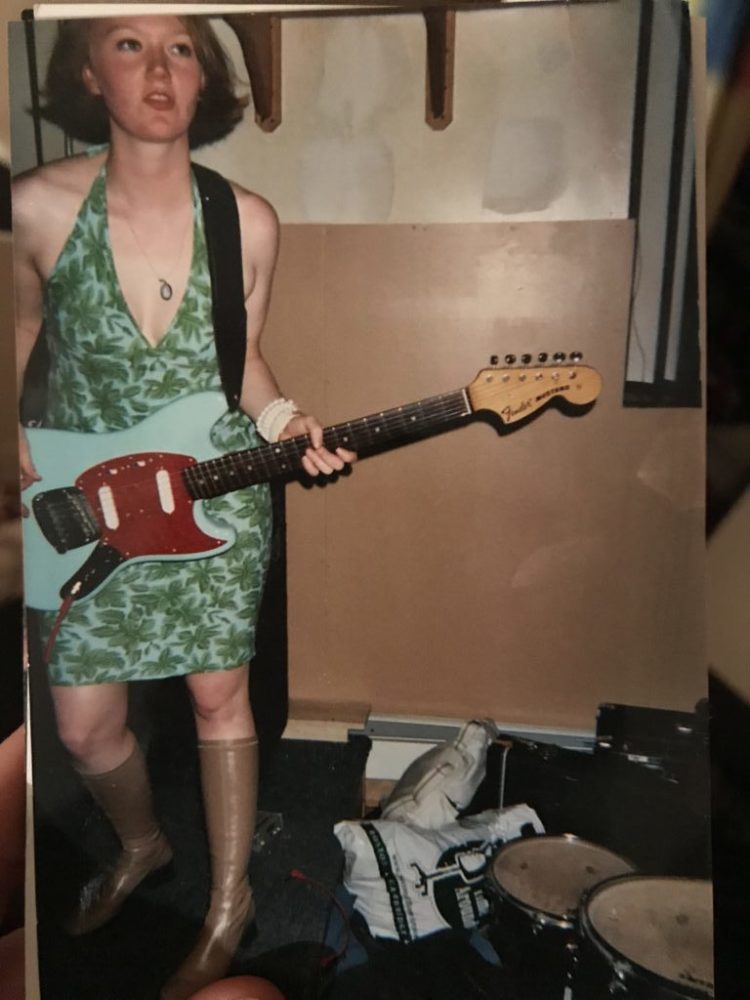

That White holds on to this lyric and savors it isn’t surprising, as I learn she wanted to be a writer when she was a child. “Of course, when you’re a pre-teen writer, it’s all crap, but my family was very supportive of me, and they’d hang my writing on the fridge,” she tells me. Admitting she was a “pretty smart kid”, her big, working-class family gathered around her when she was quite young, encouraging her to relentlessly pursue her interests. Those also included playing in a high school rock band – “Spork”, a “noise band” – for whom she played “guitar badly and keyboards somewhat worse.” Later, she played for the Saturday Saints, Mass (Radius), Bipolar Bears, and would occasionally jump on stage to play with Super Awesome.

Though White ended up an accomplished writer and educator as an adult, she did take a serious detour into the sciences during her formative years. “I’ve always been very influenced by great teachers. Early in my education, I had a couple of teachers – when I was 10 or 12 – who encouraged me to write. Later on, in my high school career, my best teachers were in Math and Science. I think that’s part of the reason I went down that path. To be honest, I can be a bit of a dilettante. I generally can be good at a lot of things, other than anything having to do with athletics or coordination of any kind. But I feel like I could have gone in a couple of different directions, so the interests I chose to pursue were really in response to teachers. As I look back at my life, I see these individuals who were like bumpers that I bounced off of; these teachers and mentors changed the direction of my life.”

While attending an over-crowded public high school, she exhausted all of the science classes they had to offer by the time she was a sophomore. In a study hall one pivotal day, she became frustrated that all of the students around her were goofing off, and bee-lined her way from there to the principal’s office. She promptly informed him she was leaving school for good to join the work force. “There’s nothing left for me here,” she told him. “I’m not good at being bored.”

“He was a good principal,” she says now. He helped her to enroll in the Massachusetts Academy of Math and Science, a two-year course school. Only around 30 students were accepted at a time, and each had to pass an arduous science and math exam to even make the cut. “I went from being the smarty pants of a 1,500-student public high school to a dumb ass in this very small pool of real geniuses. It was super-humbling, as I was not at all on their level of intellect.” By the time she completed the course successfully, though, she was told she could attend practically any college she set her sights on.

At the time, the young White was fascinated by the brain and neuroscience, and, though accepted at numerous Ivy League colleges, she chose to attend Brandeis University, where she was accepted into their famed Neuroscience program. While working the summer of her sophomore year there in a Neurogenetics Lab for Leslie Griffith, MD, PhD – her idol and someone whose path White wanted to emulate – she received the esteemed Howard Hughes fellowship (a sizeable sum of money) to perform a self-guided experiment in a Neurogenetics lab over the summer. “This is the only time this has happened to me in my life, because I’m perpetually late and perpetually hyper-extended financially,” White says, laughing, “but I came in ahead of schedule and under-budget.” White took the funds left over from her fellowship and sent herself on her first-ever trip to France. It proved revelatory.

Having grown up in a modest household, and having rarely eaten in a fine-dining restaurant, White found herself indulging in the life of the senses in Paris for the first time in her life. She discovered leisure, visiting museums and restaurants, drinking wine. The trip changed her life.

Upon her return stateside, White immediately changed her major to Art History. Propelled by the art exhibits she’d seen in Paris, and by discovering at the tender age of 19 the music of John Cage – especially his 4′33″, a composition in 4 minutes and 33 seconds, White fell headlong into the world of the Arts. “I had never allowed myself to live there intellectually before then,” White says now.

We add a log to the evening’s steady fire and move from plum wine to Japanese whiskey. “I’ve had a life of happy accidents,” she continues. “I did well in Art History, and won a curatorial internship at the University’s Rose Art Museum.” The Rose Art Museum offered a small but meticulously-curated post-war collection of art from the likes of Rauschenberg and Warhol. While there, White was mentored by Neil Printz, a pre-eminent Warhol scholar, with whom she would later become lifelong friends. “He was at my wedding.”

Upon graduating, Printz put White in touch with the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, where White got her first curatorial job out of college as a Fine Arts major. “I quickly realized that there was really no way to make money working in museums or in the Art History world.” Having occasionally worked in wine stores throughout college to supplement her income, White once again got a job at a wine shop to make ends meet. All the while, she continued to perform in rock and pop bands, and even recorded two albums during that time, but never became competent enough at music to make a go of it. “It was all just for fun.”

Like other areas that captured her interest, White pursued wine as if it was an academic subject. She immediately set out to learn about the world’s most storied wines and spirits. “At the time, all I drank was cheap Bordeaux and cheap scotch because that’s what I thought I was supposed to do to learn about wines. Because all I could afford was this cheap stuff, I just didn’t get what the fuss was all about.” After saving up some money, though, and taking herself to a “nice dinner in Beacon Hill”, a sommelier sold her a bottle of white Châteauneuf du Pape. “I was all of a sudden in this warm, fuzzy, low-acid zone of Rhône whites – John Kongsgaard once described Rhône whites as ‘hugging you,’ – and I suddenly felt comforted by those varieties. So I kept at it and kept working in wine stores. I decided I could make a living in wine, and I enjoyed the lifestyle. It also provided the perfect intersection of everything I loved: academia, travel, languages, art, history. I’m also kind of high-strung, and for once I found a career choice that helped me to slow down. Wine has been a force for civilization in my life. It’s also an endless pursuit. You can never really master it.”

It was during another trip to France, much later in her career, that White mentioned to friends wanting to write a book about the Napa Valley. “I had only been living in the Napa Valley for about six months. I was staying with the Wassermans (importers) in Burgundy. Allen Meadows was there and had just finished writing his definitive Pearl of the Cote. Clive Coates was there as well. “It was amazing, this confluence of brains,” White says. “They were all talking about writing and publishing and I sort of mentioned, meekly, that I was thinking about writing a book about Napa. There was room for it. So Becky Wasserman heard me say that, and as this tourist group visited later in the day, she introduced me as ‘Kelli White, who is writing a book on the Napa Valley’ and that was the moment I knew the book was going to happen. Once it had been spoken about out loud, to strangers, I knew now it’s on. The moment that switch was turned on, there was no way for me to turn it off.”

When White was told by the designer that the book, upon layout, would clock in at over 1,000 pages, “I went home and cried,” she says now. “I didn’t think anyone would take me seriously. I was concerned it would come across as this exaggerated caricature of wine in an exaggerated caricature of a book. Was it going to do the opposite of what I intended? Instead of delivering thoughtfulness and gravitas to a region that maybe wasn’t being taken seriously in the right ways, was I just piling on top of existing stereotypes?” Though she is grateful the book has been very well received – by literary critics and the industry itself – the one criticism it regularly receives is the size of it, that it’s a bit unwieldy. For me, the size of the book makes perfectly good sense; a region as sweeping and successful in its ascendency seems to merit its own tome. My copy at home is dog-eared from constant referencing. It is a particularly great resource for its tasting notes of older, rare, historic Napa Valley wines.

As the evening progresses, White pauses to commandeer the sound system and toggles through a line-up of largely forgotten or obscure singers and songwriters. She decides to put on Lee Hazelwood, whom she informs me was briefly married to Nancy Sinatra. I ask her if that’s the guy who sang “I’m Proud to be an American”, and she says, “I don’t know who that is, but it’s not Lee Hazelwood”, and I pour us a little more whiskey. Before long, Hazelwood’s plaintive voice comes on over the sound system – an old-timey country-folk song he released in the ‘60s.

While working on her book, White continued her decade-long work as a sommelier, first at New York’s Veritas, and then later at Napa Valley’s Press. White says she has now finally landed her dream job and is currently the Senior Staff Writer for GuildSomm.com, where she regularly writes in-depth research-driven, feature length articles and teaches a handful of classes for the trade.

“Sommelier culture is complicated. When I was younger, I was very much a bratty, east coast New York sommelier, rolling my eyes at California wines and really chasing Burgundy. Then I evolved into someone who is much more omnivorous. I’m now much more in-line with the consumer,” she says. She regards this as a personal evolution. “At the beginning, you’re almost like ‘fuck the consumer’ because you want to buy wines for your own palate. ‘Here I am putting together this amazing list and most people just want some ordinary chardonnay.’ Now, though, at least for me, I have gotten to a point where you start to prioritize the act of service over your own hubris. Suddenly, when I put service first, I found my personal tastes didn’t matter as much. I stopped judging my guests, which one should never do. It’s an arc.”

Sometimes, White confesses, she sees wine lists by somms that seem almost too personal and alienating; “there’s a difference between having a point-of-view and creating a self-serving wine list. I think great wine lists have a point-of-view, a perspective, but there’s room for the consumer within good lists. A good wine list, White adds, moves “beyond the us-versus-them mentality that some somms can have and towards a middle ground. I personally love how a lot of modern sommelier service has become more casual. But casual does not always mean friendly. A flannel shirt and a sleeve tattoo can be just as alienating as a formal suit and tastevin, if the wearer is talking down to you because you aren’t familiar with the pet nat they’re into. That’s not to say one shouldn’t be excited about something they’re keen on, but ultimately, a sommelier is a position of service.”

White sees wine snobbery, especially state-side, as a vicarious ennobling. “We’re a country without an aristocracy. We do have a class system, though. If you’re ‘lower-class’ and don’t know what the little fork is for, then the upper class thinks they’re better than you. We have these sorts of little trappings in place. It’s subtle psychological warfare that unfortunately is played out at the dinner table. You see these types of moments in cinema a lot: someone is in an aristocratic setting and they just don’t have the right table manners. These moments cause such anxiety. And we Americans have no real royalty, so we hypothetically create these artificial moments around the table during which we try to define ourselves and others, and wine can – and often does – become a of weapon of class. It can become very elite. I think that really sucks, ultimately. It’s the opposite of conviviality, communion and community.”

White herself has been undergoing a “personal process” of lightening up about wine over the last few years. “I have a lot of friends and family members who don’t know a lot about wine. But I will drink whatever they put in front of me. I sometimes see these members of the trade who seem to have lost the art of being a Gracious Guest. You go to someone’s home with industry professionals, be they somms or from other areas of the business, and if a wine is corked, everyone around the table has to raise their hand and make a big deal about it. Or maybe it has brett. This can be very upsetting to the host who may not be in the industry, who may not understand that this was not their fault. I’m of the position that if you go to someone’s house for dinner and they serve you a flawed wine, just shut up and drink it. Be a gracious guest. Don’t force them to open something else because that just causes anxiety for the host. If I were out for dinner with relatives and they ordered a style of wine that I didn’t like – say, a really sweet, very oaked chardonnay – I would drink it gladly. I would rather do anything other than see someone I love upset or not enjoying themselves. I’d rather be punched in the face, actually.” White tries to view her customers through the same prism, and this has allowed her to “take a step back from my ego” and remember that service is about making people feel valuable, comfortable and excited.

When White is serving herself wine, which is on a daily basis, she does revel in the act of wondering and pondering about what she’ll drink. “It’s a really big part of my life. It factors into a lot of things; mood, temperature, food, company.” One of the reasons White loves being a wine educator with GuildSomm is that she can spend time with engaged, up-and-coming, inquisitive sommeliers. “I love teaching and tasting with earnest sommeliers and getting excited about wines they’re excited about. Being connected to that culture and energy is incredible. I just never want to stop doing what I’m doing now…educating young people in the trade. I don’t think I could live without that anymore.”

White does see another book in her future. Even though finishing her first book “was a real struggle, it never occurred to me to give up,” she says. “I have a real addiction to follow-through. I have friends who have opened restaurants, written books… People who have not done these types of things think there’s some kind of movie-moment where the act of completion occurs and there’s this stepping back and folding one’s arms and smiling with satisfaction. In reality, if you’re creating something you then need to sell, or you’re opening a restaurant you then need to make sustainable, or you start a wine brand you then need to promote, you don’t have that movie-moment. There’s no break in the mania. With my book, the only shallow moment of satisfaction I had was when I was first introduced as “the author, Kelli White.” I liked that. It was awesome! Super shallow and dumb point to get caught up on, but I’ll take it.”

When I ask her if she’ll write about other topics in the future, she tells me with a relaxed, confident smile that even though she has dabbled in fiction, “wine is my beat. I just love it.”

*All photos courtesy of Kelli White